It’s not edible, but it can save lives.

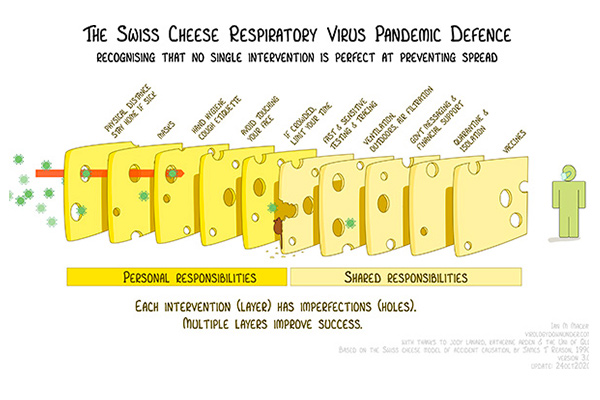

Lately, in the ongoing conversation about how to defeat the coronavirus, experts have made reference to the “Swiss cheese model” of pandemic defense.

The metaphor is easy enough to grasp: Multiple layers of protection, imagined as cheese slices, block the spread of the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. No one layer is perfect; each has holes, and when the holes align, the risk of infection increases. But several layers combined — social distancing, plus masks, plus hand-washing, plus testing and tracing, plus ventilation, plus government messaging — significantly reduce the overall risk. Vaccination will add one more protective layer.

“Pretty soon you’ve created an impenetrable barrier, and you really can quench the transmission of the virus,” said Dr. Julie Gerberding, executive vice president, Merck. “But it requires all of those things, not just one of those things,” she added. “I think that’s what our population is having trouble getting their head around. We want to believe that there is going to come this magic day when suddenly 300 million doses of vaccine will be available and we can go back to work and things will return to normal. That is absolutely not going to happen fast.”

In October, Bill Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, retweeted

A recent infographic rendering of the Swiss cheese model, noted that it included “things that are both personal and collective responsibilities”, and added the ‘misinformation mouse’ busy eating new holes for the virus to pass through.

The misinformation mouse can erode any of the layers. People who are uncertain about an intervention may be swayed by a loud and confident-sounding voice proclaiming that a particular layer is ineffective. Usually, that voice is not an expert on the subject at all. When you look to the experts — usually to your local public health authorities or the World Health Organization — you’ll find reliable information.

The Swiss cheese concept originated with James T. Reason, a cognitive psychologist, now a professor emeritus at the University of Manchester, England, in his 1990 book, “Human Error.” A succession of disasters — including the Challenger shuttle explosion, Bhopal and Chernobyl — motivated the concept, and it became known as the “Swiss cheese model of accidents*,” with the holes in the cheese slices representing errors that accumulate and lead to adverse events. The model became famous, but it was not accepted uncritically; Dr. Reason himself noted that it had limitations and was intended as a generic tool or guide.

*Labelled by Rob Lee, an Australian air-safety expert, in the 1990s.

Q. What does the Swiss cheese model show?

A. The real power of this infographic — and James Reason’s approach to account for human fallibility — is that it’s not really about any single layer of protection or the order of them, but about the additive success of using multiple layers, or cheese slices. Each slice has holes or failings, and those holes can change in number and size and location, depending on how we behave in response to each intervention.

Take masks as one example of a layer. Any mask will reduce the risk that you will unknowingly infect those around you, or that you will inhale enough virus to become infected. But it will be less effective at protecting you and others if it doesn’t fit well, if you wear it below your nose, if it’s only a single piece of cloth, if the cloth is a loose weave, if it has an unfiltered valve, if you don’t dispose of it properly, if you don’t wash it, or if you don’t sanitize your hands after you touch it. Each of these are examples of a hole. And that’s in just one layer.

To be as safe as possible, and to keep those around you safe, it’s important to use more slices to prevent those volatile holes from aligning and letting virus through.

Source

Siobhan Roberts

The New York Times

December 5, 2020

Have a story to tell or news to share

Let us know by submitting a news story, an article, a review, a white paper and more …

Submit